In building a 3-channel RC plane, I found it was necessary to learn the basics of aerodynamics. Not for constructing the plane itself, but to make sense of why I keep crashing it. This blog will document everything I learned in this regime of knowledge.

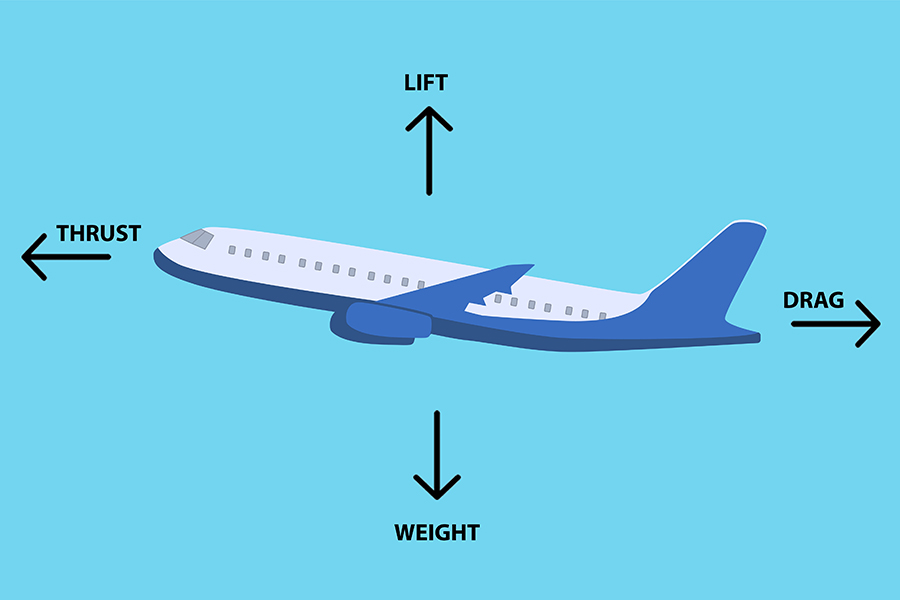

(Courtesy Pilot Institute)

There are four main forces that act on a plane (RC or otherwise). These are thrust, drag, lift, and weight. Thrust is the forward force produced by the motor and propeller. Lift is the upward force generated by the wings. Weight is the downward force due to gravity. Drag is the force from air friction that opposes the plane’s motion. You can see that for each force, there is a force acting in the opposite direction.

When the aircraft has each opposing force balanced (i.e. Thrust = Drag ; Lift = Weight), the plane is in steady, unaccelerated flight. In this motion, the plane moves forward at a constant velocity, with no acceleration whatsoever in any direction, and maintains a constant altitude.

Any intentional maneuver done by the pilot (e.g. a turn or a climb) is simply a controlled imbalance of these four forces.

Let’s talk about how the wings generate lift.

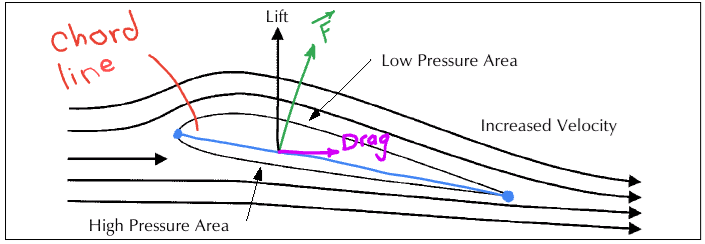

(Courtesy Physics Forums — drawn on by me)

The above diagram shows the side of a wing, a shape known as an airfoil. In the diagram, we see the flow of the air stream around it, which imparts a net force F (in green) on the airfoil. F is called the aerodynamic force and can be separated into two components: lift and drag.

The amount of lift generated depends upon both the velocity of the air stream and the angle that the chord line makes with the air stream (called angle of attack). Generally, if the angle of attack stays within ±10°, there is a direct proportion between angle and the amount of lift generated. That is, increasing the angle increases the lift; decreasing the angle decreases the lift. If you have ever stuck your hand out of a fast-moving car, you have no doubt pretended your hand was a wing and noticed these phenomena.

What happens if you exceed this threshold for angle of attack?

This:

(Courtesy of a Wikipedia page)

Here the angle of attack has exceeded the ±10° angle, and the airflow has separated because of it. This is called stalling. The separation causes lift to decrease and drag to increase. In other words, you fall out of the sky.

I have an intuitive sense of this unfortunate reality. It is the reason why I spent three days repairing two RC planes.

What causes lift in the first place? Because of the way the airfoil is designed, air particles flowing over top of the wing will move faster than those flowing underneath. From Bernoulli’s principle, we know that faster-moving air leads to lower pressure, while slower-moving air leads to higher pressure. The pressure difference (along with other things) causes the aerodynamic force, F, of which one component is lift.

For a 4-channel RC plane, it has ailerons, a motor, a rudder, and an elevator. Each of the control surfaces controls one of the three axes of rotation.

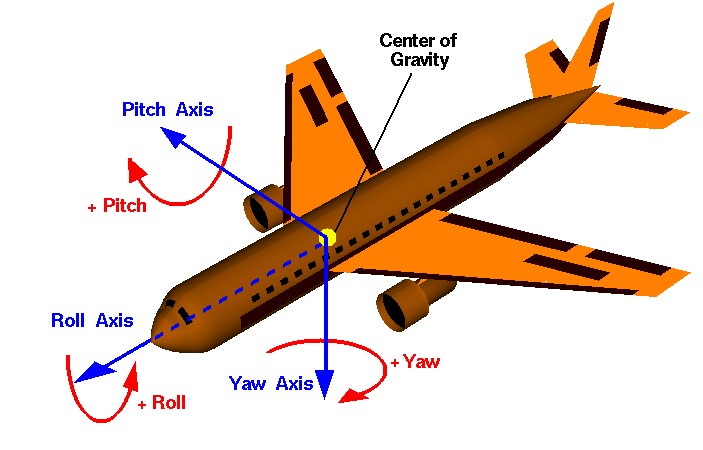

(Courtesy NASA)

The three axes of rotation all pivot from the center of gravity. They are pitch, roll, and yaw.

Pitch is the motion of tilting up and down. Roll is the motion of spinning. Yaw is the motion of tilting side to side. The elevator controls pitch, the ailerons control roll, and the rudder controls yaw (but also influences roll).

I didn’t expect building an RC plane to teach me so much about airflow, pressure, and why gravity always seems to win. But every crash made one thing clearer: flying isn’t just about putting pieces together; it’s about understanding how and why they stay in the air (or don’t).

This is just the beginning of me scaling the RC learning curve. I will continue to share what I learn in my RC hobby as well as other topics of interest (look out for the upcoming calculus blog post). Prepare for a lot of (possibly) exhausting details.

Ad caelum!