Calculus provided relief from the two-thousand-year decline in mathematics that proceeded the death of Archimedes.1 With its tools to analyze motion, change, and infinite series, calculus was a novel interpretation of reality and, to many, impossible to understand. Probably more often than not, students have gone into studying this subject with rumors of its difficulty floating in their mind, and, accordingly, they find it intractable. After years of calculus study, however, I find this widespread impression to be false.

I cannot generalize my claim over the entirety of calculus just yet, considering I am still only on Calc II, but I thoroughly believe that what I have to say is applicable to all students who are new to the subject.

Background

Since the 10th grade, I have been rigorously studying calculus. This was an unconventional place to begin since most students start learning the subject as a junior, senior, or college student (if they learn it at all, that is). Despite the breach in etiquette, however, my understanding flourished.

Having this reasonably smooth journey into calculus, I never quite understood people’s hesitation with the subject. Even stranger, I have heard some describe the transition of algebra to calculus as orders of magnitude more difficult than the transition from arithmetic to algebra. For me, though, I had more difficulty with algebra in 6th grade than calculus in 10th.

Understanding that I do not even remotely qualify as a genius, why was it that my 14-year-old self had no trouble with calculus, but a multitude of older students struggle with it.

The Proliferated Rumor

One reason that was alluded to earlier is culture. There is no shortage of people who will tell you that calculus is complicated, that it is not intuitive, that it is next-to-impossible to understand. It is probably more difficult to find someone to say otherwise.

Let me make my stance clear: I am not arguing that calculus is immediately accessible; I am arguing that the subject is fundamentally simple and not far from intuition. If this was not the case, humans probably never would have discovered it!

The other problem, of course, is having a teacher who is not enthusiastic about it themselves or perhaps doesn’t understand it. This is far too common. With a bad teacher, the student cannot parse the subject and will be left with the impression that the difficulty is an inherent property of the subject, instead of just the environment he or she learned it in.

My philosophy, which I think applies to nearly everything, is that complex things are usually just a lot of simple things densely packed together. It is your job as a student to unpack it.

If the reader is just starting calculus, I recommend skipping to the General Advice section below. The next two sections will be explanations of concepts commonly considered to be hard, but are actually straightforward.

Delta-Epsilon Proofs

Of all the concepts discussed in Calc I, the concept considered hardest is the –

(delta-epsilon) proof; yet, all the proofs you have to do will follow the same procedure. Here, I will attempt to explain the simplicity of

–

proofs via an intuitive explanation and examples.

What is it?

Everything in math needs to be shown that it logically follows from the basic axioms of math. We demonstrate this via mathematical proofs. The –

proof is the proof of a limit.

Definition

The definition of a limit is as follows (where and

are real numbers).

Let be defined for all

in some open interval containing the number

, with the possible exception that

may or may not be defined at

. We will write

if given any number , we can find a number

such that

satisfies

Explanation

To the novice, this can be unsightly; however, this is actually quite simple.

Limits are trying to find the value that is converging to as

is converging to

. They are thus only concerned with the function behavior when

is near but different from

. This is why the definition is constructed with ranges around

and

.

In simple terms, the definition states that no matter how small some number is, eventually, as

gets really close to

, the distance between

and

(i.e.

) will be less than

. Thus,

could be equal to

units, and, eventually, as

approaches

, the distance between them will become less than

. Further, the limit definition states that as

is approaching asymptotically close to

, the corresponding

is getting closer to

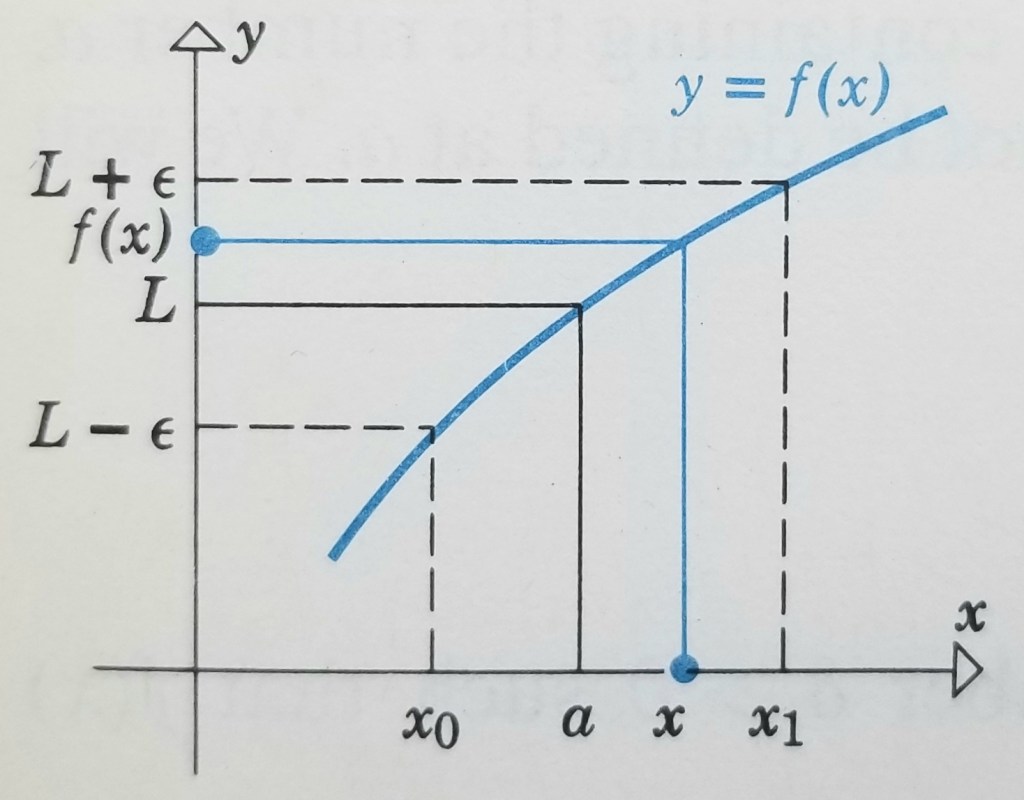

(see figure below — the

range around

is a subset of

and is not shown). Indeed, as

gets closer and closer to

,

gets closer and closer to

such that no matter how small some positive number

is, eventually the distance between

and

will be smaller than it.

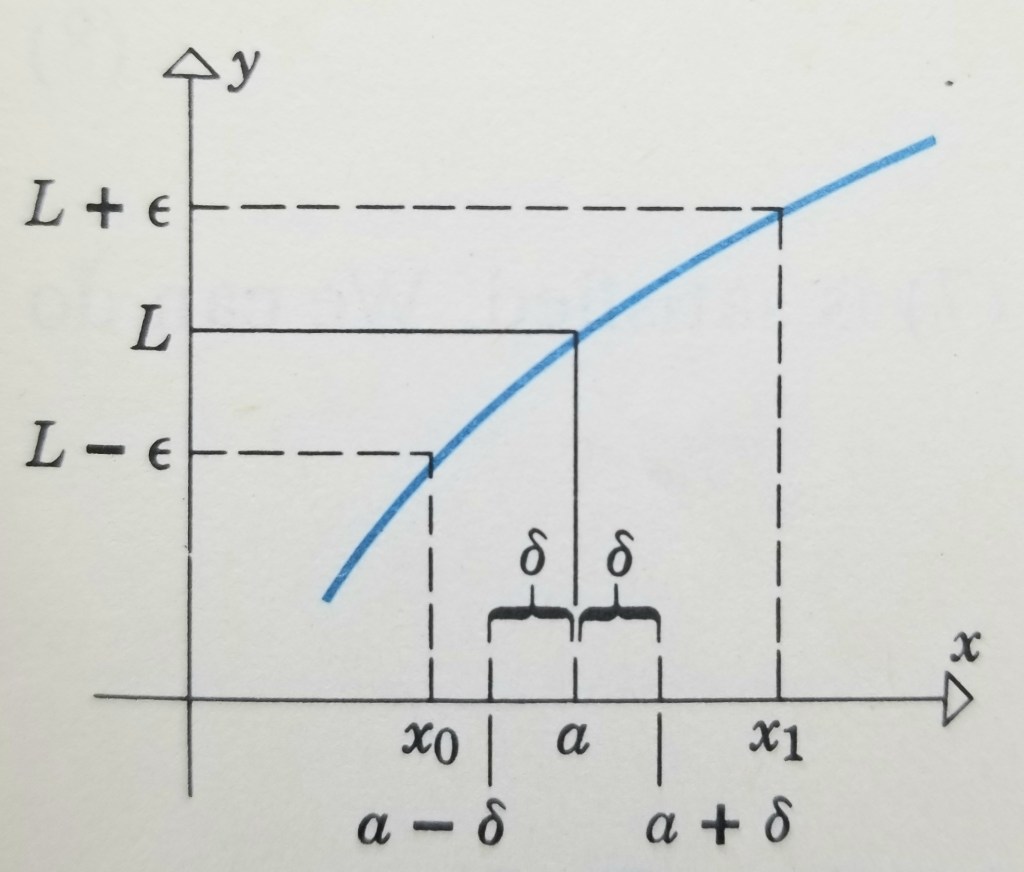

Below illustrates the range. As you can see, whenever the distance between

and

is less than

, the distance between

and

is less than

. In other words, when

is in the

range,

is in the

range.

Why is the condition greater than zero, but the

condition not?

The condition is not greater than zero because

could assume the value

at some point as

approaches

. In most diagrams, you will usually only see

(as for above), but this is not always true. For example, the constant function,

, will assume the value of

as

approaches

. If we decided to stipulate that the distance between

and

has to be greater than zero, we would not have a very good definition because we would not be able to take the limit of constant functions.

The condition is greater than zero because

is not allowed to equal

. A limit is supposed to tell you what value a function seems to be approaching. It thus only looks at the function values of

around

. Considering the value when

equals

would defeat the purpose of the limit.

What the problems consist of and how to solve them

Delta-epsilon proof problems that are given to the already struggling student generally look like this: “Prove [insert some limit here].”

To solve these, you will have to show that the given limit statement obeys the limit definition, viz. for every satisfying the

condition there exists

satisfying the

condition. In order to show this, you will have to plug in the given

and

into the

condition and plug in the given

into the

condition. After this, you have to find a formula that connects

and

. Now, via the formula, whatever

you choose, there is automatically a corresponding

. This satisfies the definition (read the definition again if what I just said is confusing).

That’s literally all. You just have to find a formula that connects and

.

The trickiest part, however, is going about finding the formula. To do so, you will have to algebraically manipulate the condition until it looks like the

condition. When you reduce the

condition with its restriction down to the

condition, you will get a restriction on the

condition. Earlier, we represented the

condition’s restriction by the Greek letter

, since we didn’t know the restriction at the time. Now, from this reduction, we know the restriction. We can then write

is equal to this restriction, which is in terms of epsilon. That’s the formula.

This will make more sense with some…

Examples

Prove

Soln. We must show that given any positive number , we can find a positive number

such that

satisfies

(i)

whenever satisfies

(ii)

As stated earlier, to find the formula for , we must manipulate the

condition until it looks like the

condition. We can rewrite (i) as

or

(iii)

Remember: We have to choose a value for such that whenever we know

, we know

. What (iii) is telling us is that the

condition is less than

. Earlier, in (ii), we defined the boundary of the

condition to be

. This

was just a placeholder for a value we didn’t yet know. Now, we have the boundary for the

condition as

. Thus,

We have just shown that for a given satisfying (i), there exists a

satisfying (ii). In other words, the conditions of the limit definition are satisfied. Therefore, the limit is true.

Done! It has been proven.

To analyze what we just did: We assumed that for any satisfying the

condition there is a

satisfying the

condition. We didn’t know whether this was true, but we assumed it was and showed that this assumption was, in fact, correct. We showed this by using some algebra to reduce the

condition down to the

condition. From this, we found the restriction of the

condition in terms of

. This condition is such that, when

satisfies it, the distance between

and

is less than

. We then deduced that

must be equal to this restriction. In this way, we satisfy the definition that for every

, there is a corresponding

.

Limit proofs of linear functions are about as easy as –

proofs get. Any further and you have to be more creative with the algebraic manipulations of the

condition. However, it is still the same underlying principle; i.e. find

in terms of

.

A bit harder of an example

Prove

Soln. This is more abstract than the last one, but our goal is still the same. Assume we are given an . Find that there is

for every

such that

(i)

whenever

(ii)

We need to manipulate the condition so that it looks like the

condition. This way we find the restriction on the

condition. That restriction will be equal to our restriction placeholder,

. Thus, we do as follows:

Okay, so we have our condition expressed here, which is good. However, we also have this other factor,

. It’s fine to have factors that are constant, but this one varies with

. The bad thing about this is we don’t really know its behavior. In general, there are cases where we can write

as

, where

is a non-constant function and

is the

condition. WE DON’T KNOW THE BEHAVIOR OF

!!! It could very well be that, as

approaches

, the value of

blows up to infinity. If that happens, it doesn’t matter that

is getting smaller;

ruins any hope of

. Therefore, we cannot isolate the

condition. We must restrict (or bound) our non-constant factor’s value to be such that the product,

, remains less than

. How do we do this? We constrain the value of

to only a set range of values, wherein the value of

is such that the product is less than

. The range of

is determined by allowing

to equal some value, say,

:

Let . Then,

The boundary value that has in order to satisfy

is

. Thus, the range of

when

equals 1 is

This is our boundary wherein the product is less than

:

Now, we need a range of where

is indeed less than

. Thus,

But, hold on. We had put . We put

to represent the restriction we had yet to know. But now, we know the restriction for

is

. Thus,

With this, no matter what value of we are given, we know the value of

.

This value of satisfies the condition that

(obviously), but we also need the condition of

to be satisfied. Otherwise, our non-constant factor wouldn't be bounded. (The following answer is seen to be valid from the observation that for any value of

we choose, any value smaller than that would also work.)

Thus, for the value of we choose the minimum of

and

. This is denoted as

1 ,

We interpret this result as “Whatever value is smaller, we make delta equal to that.” This way, (i) is satisfied whenever (ii) is satisfied.

Q.E.D.

N.B. The choice of as the value of

was arbitrary. It could have been

or

just as well, but the standard choice is

.

Harder example

Prove

Soln. We assume that for any given , we can find a

such that

(i)

whenever

(ii)

We must manipulate the condition to look like the

condition, so that we can find the restriction on

. This restriction will be equal to

. Thus,

We have rewritten (i) to have (ii) as a factor. But… oh no. Not again! We have a non-constant factor, . As I said before, we must bound this factor in order to assure ourselves that the product is less than

when

approaches

. To do so, we let

(

can’t equal 1 because the value

goes ad infinitum when it approaches

), find the range of

that satisfies such a restriction, and then find the boundary of the

. This way, the product,

, remains less than

.

Let ,

The range of that obeys

is

,

. To obtain the boundary for

, let us take the reciprocal of the inequality and multiply by 2:

Thus, . This boundary is such that, when it is obeyed, the product,

, is less than

. It is then true that

We need to choose a restriction of that allows this to be true. If

remains less than

, the strict inequality is satisfied. Thus,

But hold on… we made . That

merely represented the restriction of the

condition. Now, we have found the restriction of

to be

. Thus,

With this, no matter what value of is given, we know the value of

. That is to say, for every

, there exists a

such that (i) and (ii) are satisfied. We need to include, however, our arbitrary value of

, so that the non-constant factor remains bounded, which requires

. We also need

. We pick whichever value is smallest. Thus,

Q.E.D.

In conclusion of proofs

For the delta-epsilon proof, the goal is to choose based on a given

so that

. The answer will be a formula for

in terms of

. There are cases where this procedure is made difficult by a non-constant factor popping up during our reduction of

to

. The goal, however, remains the same.

Optimization Problems

Problems concerned with finding the most optimal way to perform a task are called optimization problems.

It’s strange to learn that many people find these to be difficult, considering a large swath of optimization problems are simply finding the largest or smallest value of a function and determining where the value occurs. I personally love this part of calculus. It requires logic and a healthy amount of creativity.

What are you required to do?

For optimization problems, you will have a constraint that is used to isolate one variable and a formula/function to maximize or minimize. You thus do as follows: Using the constraint, express the function in terms of one independent variable. Find the range of values that the variable can equal such that the context of the problem is satisfied. Differentiate the function. Set the derivative equal to zero and find the value of the variable that leads to such a condition being true. You now have candidates for the maximum or minimum. Find which one is the relevant extremum.

Why do we set the derivative equal to zero?

Since we are trying to find the relative extrema of functions, we have to solve for points that have the properties of relative extrema. All points that are relative maxima or minima have derivatives of zero. In other words, the tangent line at a relative extremum is horizontal. We thus solve for points that have derivatives of zero and narrow down the candidates to the actual extremum.

Examples

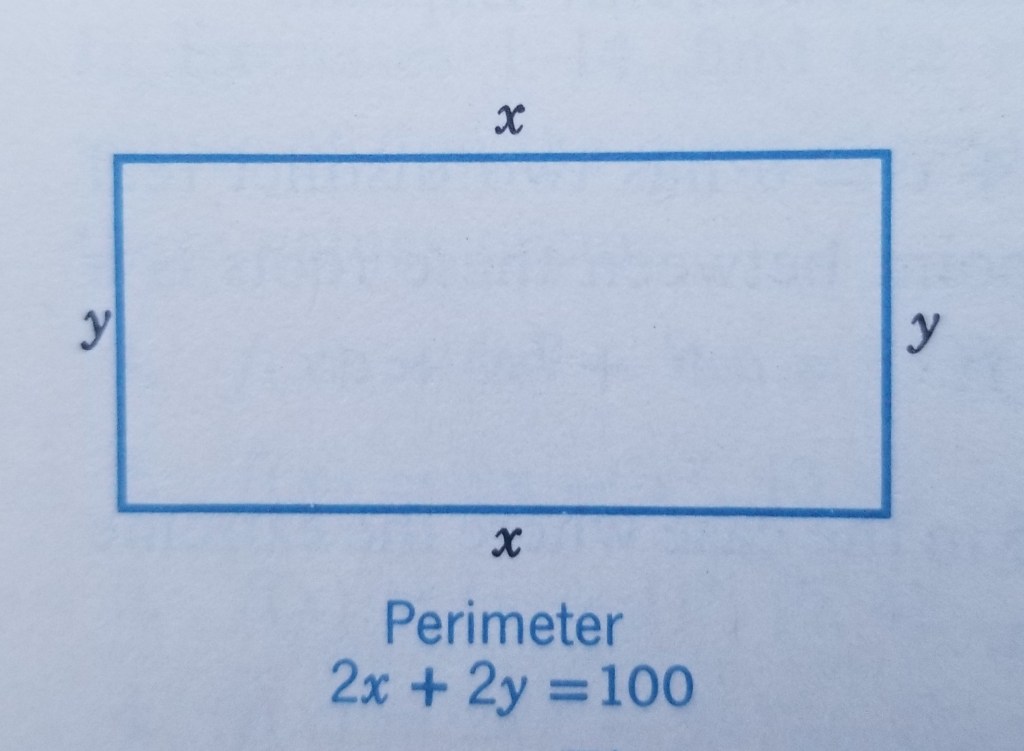

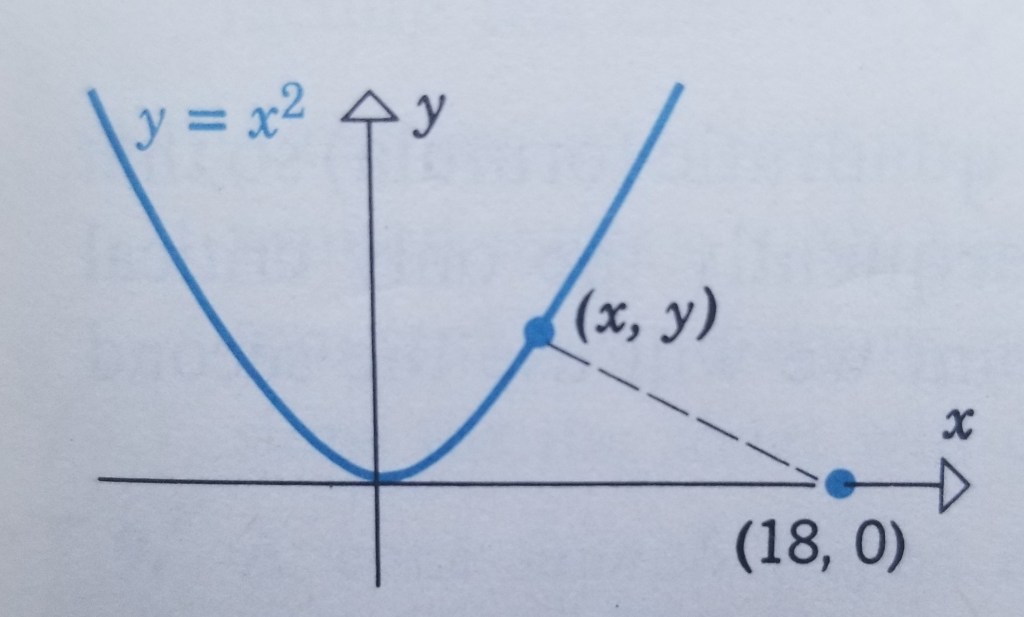

With reference to the diagram below:

Find the dimension of a rectangle with perimeter 100ft whose area is as large as possible.

Soln. Let

Then

Since the perimeter of the rectangle is 100 ft, the variables and

are related by the equation:

Notice, we are told to find the dimensions of the rectangle whose area is largest. We thus have to solve for the dimensions when the area is at a maximum. The formula is the formula we must maximize, but we need it in terms of just one variable. To do this, we use our relation between

and

(this is the constraint I talked about earlier) to solve for one variable.

Using substitution,

Because represents a length, it cannot be negative. Additionally, since the two sides of length

cannot have a combined length exceeding the total perimeter of 100 ft, the variable must satisfy

It can’t equal because we’d then have a one-dimensional line with no area. It can’t equal

because then

would equal zero and that would once again just be a line. (Some opt to include those as endpoints, since they are mathematically possible. However, I am in the camp that believes humanity should not waste its time by considering practically impossible things.)

Differentiate :

Create the conditional statement of (to find the relative extrema) and solve for values of

that satisfy the condition.

The solution is . From the relation,

.

The rectangle of perimeter 100ft with greatest area is a square with sides of length 25ft.

A bit harder of an example

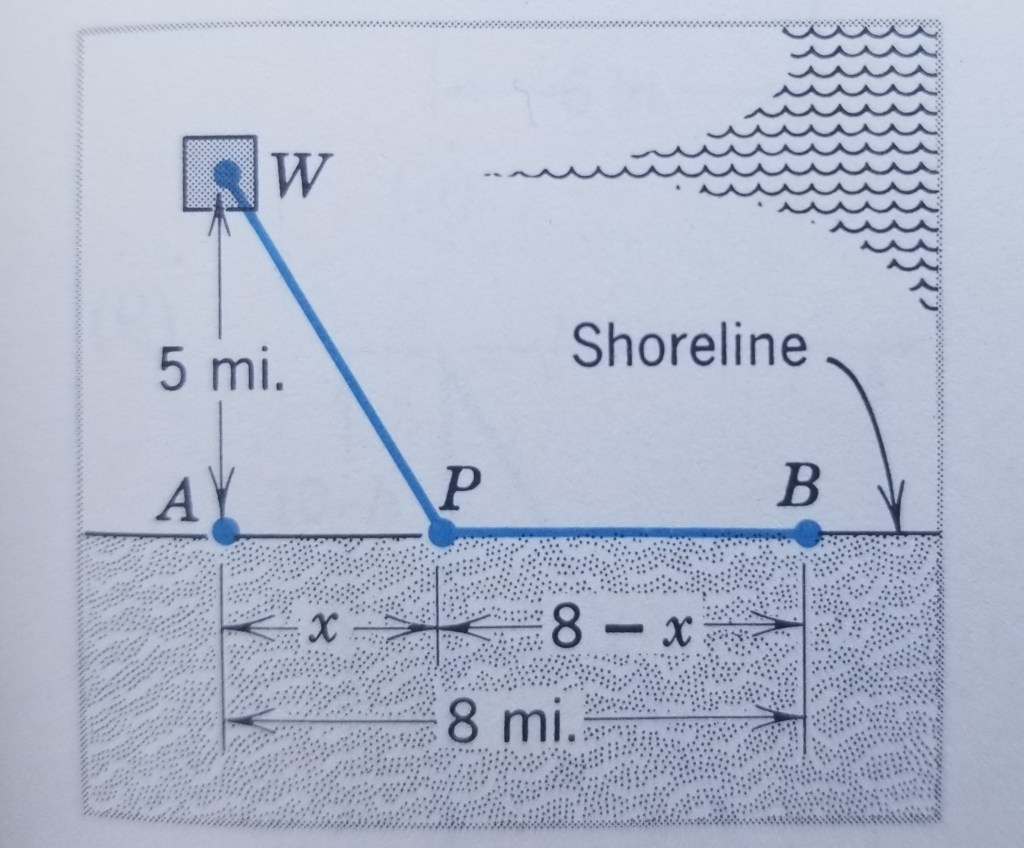

With reference to the diagram below:

An offshore oil well is located in the ocean at a point W, which is 5 mi from the closest shorepoint A on a straight shoreline. The oil is to be piped to a shorepoint B that is 8 mi from A by piping it on a straight line underwater from W to some shorepoint P between A and B and then on to B via a pipe along the shoreline. If the cost of laying pipe is $100,000 per mile underwater and $75,000 per mile over land, where should the point P be located to minimize the cost of laying the pipe?

(Remark. The shortest distance between W and B would, indeed, be a straight line. Even though this uses the least amount of pipe, all of it is underwater, which would be expensive to lay. Similarly, a pipeline from W to A to B uses the least amount of expensive underwater pipe, but uses the greatest total amount of pipe. Thus, it is actually best to make a pipeline that goes from W to some point P between A and B and then go on to B. This would incur less total cost than by piping to either extreme location.)

Soln. Let

We see from the diagram that the distance of pipe underwater from W to P is

(i)

We also see that the distance between the P and B is

(ii)

From (i) and (ii), the total cost (in thousands of dollars) for the pipeline is

Because the distance between A and B is 8 mi, the distance between A and P must satisfy

(We include the endpoints, since they are practically possible.) In this problem, we have no constraint, which is fine since the formula is already in terms of one variable. Differentiate :

Equating to zero,

or

or

The number is not within our range, leading

being the only stationary point. The minimum thus occurs at one of the following points:

Plugging these values into the cost formula yields

When

When

When

We need the value of such that

is a minimum. The answer is therefore

.

The distance of P, the point onshore where we pipe the oil to, must be mi away from A in order for the cost to be a minimum.

A harder example

With reference to the diagram below:

Find a point on the curve that is closest to the point

Soln. The distance between

and an arbitrary point

on the curve

is given by the Euclidean distance formula:

Since lies on the curve,

and

must satisfy

. Thus,

(formula to minimize)

Because there are no restrictions on , the problem reduces to finding a value of

in

for which

is a minimum, provided such a value exists.

I am going to use a helpful math trick that is based on the following fact: The maxima and minima of a function occur at the same points as the square of that function. Thus, the minimum value of and the minimum value of

occur at the same value.

Differentiate :

Equate to zero:

The only real solution to this conditional statement is . The second derivative test yields a positive result when

is plugged in. Thus, the point on

that is closest to the point

is

In summary of optimization problems

These types of problems almost always follow the same procedure.

Step 1: Label the quantities relevant to the problem.

Step 2: Find the formula to be maximized or minimized.

Step 3: Using the conditions stated in the problem to eliminate variables, express the quantity to be maximized or minimized as a function of one variable.

Step 4: Find the interval of possible values for this variable from the physical restrictions in the problem.

Step 5: The rest is mechanical. Differentiate the function. Equate to zero. Find the values of the variable that satisfy that condition. Determine which value is correct via the range and whether it is the appropriate type of extremum.

General Advice

This subject is not as hard as you have been led to believe. Certainly, it is hard to intuit at first, but with many hours of focused study, it will start to become clearer. People who experience zero friction with intellectually-taxing studies do not exist; those you think do simply work hard and often.

For any student just beginning this wonderful yet difficult subject, the following list might provide good advice:

- Read respected books – One reason why my 14-year-old self was able to understand calculus quickly was the literature I used. If you are struggling with this subject, I highly recommend Thompson’s Calculus made easy. The book explains everything extremely well and acknowledges its quasi-complexity. It is not, however, a formal math book, and you should try to get through it as quickly as understanding permits so that more formal textbooks can be tackled.

- Don’t be scared by weird-looking symbols – There are a lot of strange ones in calc; however, they all have precise meanings and will be comforting to see once they are learned.

- Master algebra and trig – Calculus definitely requires a firm understanding of algebra and trigonometry, so be sure to get sufficiently good at those. For me personally, however, I started with only a basic understanding of trig and was able to learn calc efficiently. If I ran across any trigonometry concept I didn’t recognize, I would divert time to learn it.

- Ask questions – It is more productive to be confused and know specifically why than to just be confused. Try to reduce your confusion to specific questions that can actually be answered and then seek answers either by thinking on your own or by consulting an external source. (If you don’t understand parts of this blog, apply this method.)

- Don’t lose the plot – The simplicity will beget complexity. You cannot forget that, at its core, it is made up of the same simple things.

In summary, just work hard. There is no substitute for work, and a skill is impossible to obtain without practicing it frequently. You will often hear mathematicians speak of the beauty of their subject. This probably sounds strange to the layperson, but rigorous study of calculus will make that claim less unreasonable. You will start to see the underlying simplicity of it all and realize why it has to be the way that it is.

And after you have finished the material and are comfortable with the subject, be proud to have such a well-thumbed book on your shelf. It is a very satisfying sign of progress.

- This is an oversimplification of those 2000 years. The decline was primarily in the Western world. Most of the progress made in that time was by China, India, and the Islamic world. Also, the decline is considered to have actually ended about 100 years before the discovery of calculus, with Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus. ↩︎