Despite having slept only 5 hours the previous night, my mind was incredibly alert. Indeed, the anticipation of flying Tiberius inspired a certain tenacity in my actions that day.

Just one week prior, on August 3, I had attempted to rebuke gravity with the maiden flight of my first RC plane, Augustus. Unfortunately, due to both a poor CG and an excessive weight with no commensurate thrust, the warping of spacetime would return my dismissal, leaving Augustus in pieces.

Today, however, would be different.

Applying my newly-developed engineering habit of iterative problem-solving, I learned everything I could from Augustus’ flights and implemented appropriate solutions into Tiberius. With its lighter, more streamlined design, success was certain. At least more so than last time.

Heading to our local RC field at 9:00 a.m., my father, brother, and I prepared for the first successful flight of one of my RC planes. Of course, saying that I was completely confident in such nominal proceedings wouldn’t be accurate. As an optimistic forecast, I gave a 60% chance of success.

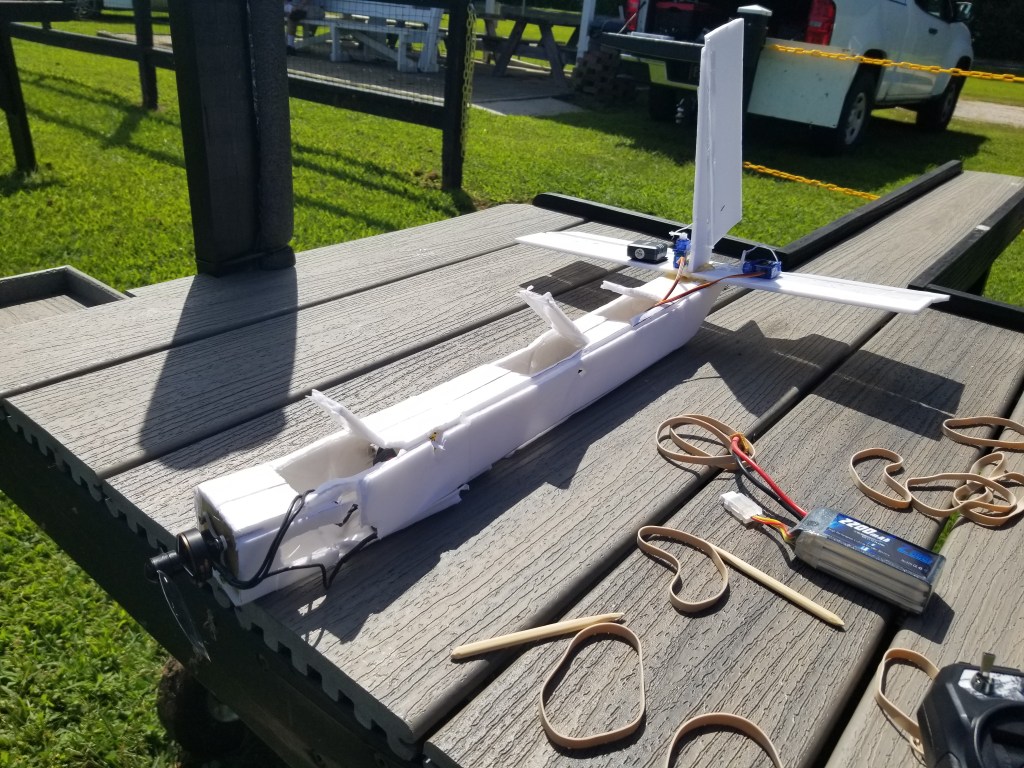

Upon arriving, we unloaded Tiberius from the car and placed it comfortably on a work bench.

After attaching the wings and connecting the 3S LiPo battery, I tested the two control surfaces as well as checked the motor’s direction of spin. Pleasantly, all worked well.

Having my go for flight, Tiberius was carried in the hands of my father toward the grass runway. After a range check, he held it high in his hand, and I started pushing the throttle up to its highest point. Pushing the elevator control down, I motioned to my father to throw…

Perhaps it’s hard to tell from the screenshot, but this is bad.

That tiny rectangle just above the corn is the battery. Poorly placed at the rear opening of the plane, it had immediately disconnected and fell out, leaving Tiberius to fall down powerless.

Luckily, this was not fatal. In fact, the damage was little more than a snapped rudder.

The rudder had cracked at a line of discontinuous elasticity (I read an engineering book once; I think this is the correct terminology) caused by hot glue that connected two pieces of it together.

As a fix, we applied more hot glue and wrapped an excessive number of rubber bands around the battery, hoping that it would be tight around the walls of the plane and not slip out.

Assuming our previous position, we attempted a second flight…

Even though the battery didn’t fall out, I committed a cardinal sin in aeronautics: I made the plane tail-heavy. As you can see here in the screenshot, Tiberius is pitched dangerously up.

What caused this improper CG position? The battery. Being in the rear, it compromised any hope of stability. However, perhaps by the grace of the sky god, the plane glided down perfectly undamaged and in an upright position.

After seeking counsel with some seasoned hobbyists who were present, I was informed that the center of gravity had to be ~1.25 in. away from the leading edge of the wing. To achieve this, they recommended putting the battery near the front of the plane, which, apparently, is a standard convention.

Removing the wings and contorting my hands through the fourth dimension, I connected the battery into the cramped space near the nose. After the seasoned hobbyists checked the center of gravity, they thought it would have to go up further but that I could try it now.

Therefore, I went for a third test flight…

This was perhaps the strangest test flight.

Although the screenshot doesn’t make it clear, Tiberius spun 180° clockwise while in the air. I can only assume this was caused by a gust of wind or perhaps my father throwing it in a strange way. In either case, it still crashed into the ground.

Despite landing upside down, it was in remarkably good shape, with even the rudder still fixed in position. Once again, I sought advice from the seasoned hobbyists, all of whom recommended the battery be pushed up further.

Bringing it back to the workbench, I set the transmitter down next to the plane. Unfortunately, when I leaned over the bench to manipulate the battery, I accidentally pushed against the transmitter and turned the motor onto full throttle. Sitting on the bench, the propeller managed to strike the wooden surface and tear itself apart. Acting quickly, I shut down the transmitter; however, the damage was done.

The end of Tiberius was not on the field, as I and everyone else expected, but on the workbench.

While some might consider this ending to be worse than Augustus, I am in the opposite camp. Not only is this plane orders of magnitude better than the previous, its design achieved everything that it needed to: it crashed and gave me valuable data.

The lessons obtained from these early stages of my model aeronautics hobby can only be learned through an iterative approach: fail, learn, improve, repeat. After the flight and destruction of Tiberius, I learned a couple of things:

- Put the battery near the nose of the plane – since a plane is, by default, tail-heavy, anything that can be moved toward the nose should be.

- Have a safety protocol – if it wasn’t for the fact that the transmitter was still on, Tiberius could have been tested again and, perhaps, even flown successfully. A step-by-step protocol will prevent this from occurring again.

I suppose it’s appropriate that a plane named after a deeply-flawed Roman emperor would be structurally flawed. The next plane, luckily, is named after the relatively peaceful emperor Caligula.

Ad caelum!