While writing my calculus blog, I found (perhaps even discovered) a new way of thinking about the –

(delta-epsilon) proof. This interpretation won’t cause any kind of epistemic revolution in mathematics, but I believe it’s a helpful pedagogical tool worthy of its own blog post.

In case you have forgotten, the limit definition states the following (where and

are real numbers):

Let

be defined for all

in some open interval containing the number

, with the possible exception that

may or may not be defined at

. We will write

if given any number

, we can find a number

such that

satisfies

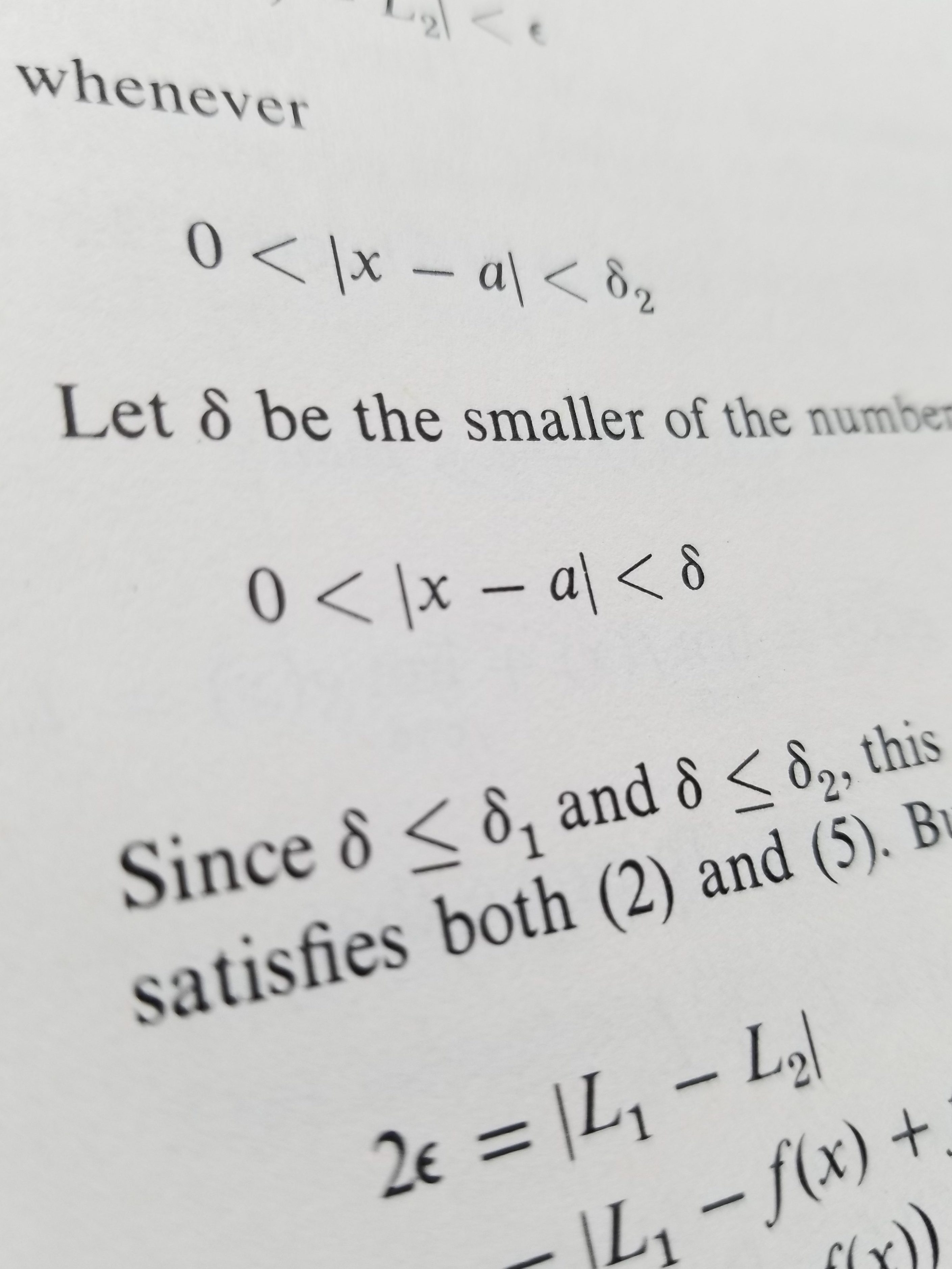

whenever

satisfies

To prove a limit statement, we have to show that the limit satisfies this definition. How do we do this? We assume exists and show that, no matter what the value of

is, there exists a corresponding

. The mechanical procedure is as follows: Reduce the

condition down to the

condition, find the restriction on the

condition, and equate that restriction to

.

Taking a simple example:

Prove

Soln. We must show that given any positive number , we can find a positive number

such that

satisfies

(i)

whenever satisfies

(ii)

To find , we must manipulate the

condition until it looks like the

condition. We can rewrite (i) as

or

(iii)

We have now reduced (i) to look like (ii). Earlier, we stated that is less than

, but now we see that it’s less than

. We thus deduce that

We have just shown that for a given satisfying (i), there exists a

satisfying (ii). In other words, the conditions of the limit definition are satisfied and the limit is true.

Q.E.D.

One of the things I always wondered when doing such computations was “How can we be certain that the condition’s boundary was the greatest boundary possible.” That is, how do we know that there isn’t a bigger boundary that still satisfies the conditions.

Well, after a lot of intellectual struggle and Socratic rumination, I came up with a different way of thinking about the reduction of the condition that makes it obvious how this is certain.

Consider the following:

Imagine a function that takes as its input the distance between

and

(i.e.

) and outputs the distance between

and

(i.e.

).

In this view, the restriction on the condition is really just a restriction on

.

From middle school algebra, we know that we can apply a restriction on the output of a function and then reduce that output to the input. When we do this, we get a corresponding restriction on the input. This restriction is such that, when satisfied, the output restriction is satisfied. For example, let

:

Stipulating , we can find the input restriction that leads to this being true. We do that by reducing

to the input

:

Dividing by 3, we obtain

This is the input restriction that satisfies the output restriction. Notice that any value above 2 leads to an output that is greater than 6.

Thus, reducing with the

restriction will produce the input with its

restriction, a restriction which is the greatest possible. Since

is simply the distance between

and

, we are truly finding the upper bound that the distance between

and

must stay below in order for the

condition to be satisfied.

Interpreting –

proofs this way, makes our actions quite reasonable.