The warmth of spring, though currently intangible to our senses, is nearing closer, and with it, an environment favorable to the prospect of frolicking outdoors.

While the list of soon-to-be-resumed activities is inexhaustible, one particular pastime has, for several weeks, maintained a relentless occupation in my mind: bicycle riding. Even now, with temperatures firmly set in the thirties, I’ve had a strong urge to get out the ol’ bike and take a ride about. I would act on this urge now, of course; alas, my bike hangs high up on the ceiling of my garage, imposing a steep activation energy to any such decision. (Besides, riding in the cold airstream would likely remove any potential enjoyment.)

This fixation started while I was studying the rotational dynamics section of my physics course. Pivoting from abstraction to praxis, it began to speak, at length, about the underlying physics behind bicycles—torque, static friction, rotational equilibrium, the whole lot. As I continued to read, the mental image of a bike tire rolled around in my head. I started to think about how the chain interacts with the sprocket, how a person’s foot causes different amounts of torque when at different pedal positions, how falling results when the center of mass isn’t aligned with the axis of rotation.

Needless to say, I began to crave for a bike ride.

For now, though, I’ll settle with just writing about the physics governing the activity.

Looking at the tire above the ground

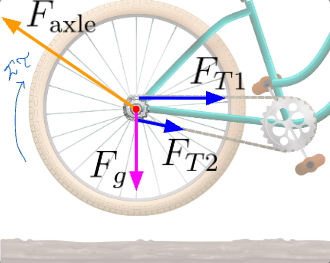

Suppose I conjured up the might to overcome that activation energy, took my bike down from the garage ceiling, and set the front wheel down while holding the back above the ground. I then apply a clockwise torque to the wheel via the pedals.

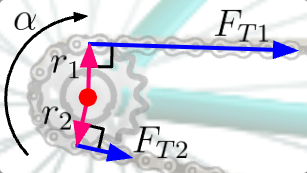

Due to the pedals turning, two opposing tension forces, F_T1 and F_T2, arise. Both tension forces act perpendicular to their position vectors, r_1 and r_2, as seen below.

F_T1 tries to cause a clockwise torque, while F_T2 tries to cause a counterclockwise torque. Since we know, however, that a net clockwise torque results, F_T1 must be greater in magnitude.

This isn’t abstract. You can readily observe this fact by looking at the chain while the tire is spinning. The top chain is taut, but the bottom chain has some slack.

Going back to the first force diagram, you can see that there are two other forces acting on the tire. There’s the force of gravity, F_g, and there’s the contact force exerted by the axle on the wheel in response to the wheel being pulled down by F_g and to the right by the tension forces. (A contact force is the force that an object exerts on another object that’s in contact with it.)

From inspecting the force diagram, you can see that the horizontal and vertical components of all of the forces cancel. The system is therefore in translation equilibrium. However, the system is not in rotational equilibrium. The torque caused by F_T1 is greater than the torque caused by F_T2, leading to a nonzero net torque. (Since F_g and F_axle act at the axis of rotation, they do not produce any torque.)

What actually propels a bike forward?

You can now imagine that I’m a tad bored with looking at a translationally stationary tire and so decide to set the back of the bike down and go for a ride.

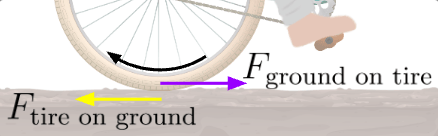

I start to pedal, which results in the bike’s acceleration, as expected. The direct cause of this acceleration, however, is not the force I’m applying on each pedal. It’s the static friction between the tire and the ground. (Note: The friction would indeed be static, not kinetic, friction because the tire is instantaneously stationary with respect to the ground. If the tire were to skid, though, then it would be moving with respect to the ground and kinetic friction would be produced.)

Since the tire is rotating clockwise (as seen above), the tire pushes the ground to the left. By Newton’s third law, this results in the ground pushing on the tire to the right with equal fervor.

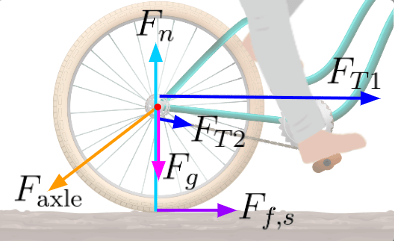

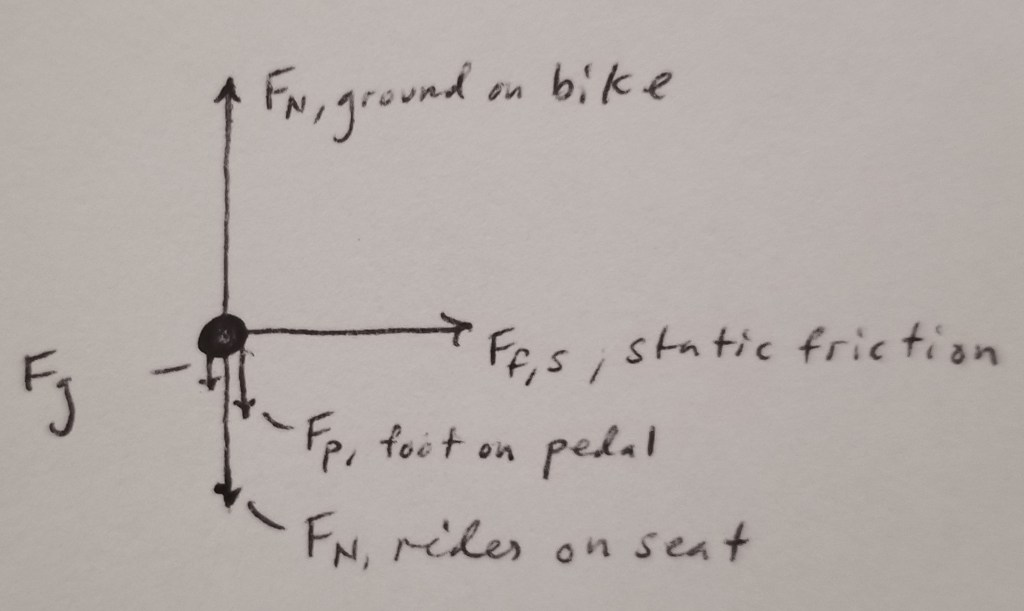

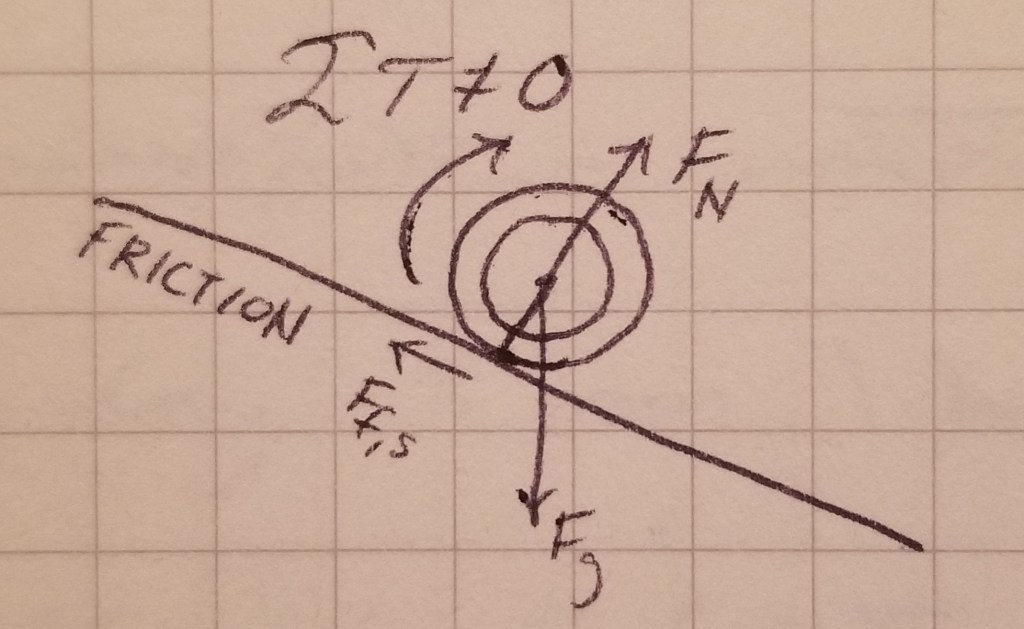

The force diagram for my bike as I pedal would look like.

The free-body diagram would thus look like

(Recall that free-body diagrams only include external forces)

The forces in the vertical dimension are balanced. However, in the horizontal dimension, there is the force of static friction which has nothing to oppose it, thus causing the acceleration that allows me to enjoy the afternoon at 10 mph.

Since static friction is perpendicular to its r, it produces torque; this torque, though, opposes the torque produced by the top chain of the bike. This means that if I’m applying a certain torque on the pedals when the bike is on the ground, the the net torque will be less than if I held it above the ground (since static friction wouldn’t be opposing it). Thus, the back wheel would have a greater angular speed when above the ground. Nevertheless, we have static friction to thank for the fact that we can accelerate at all!

Thinking about things from the front

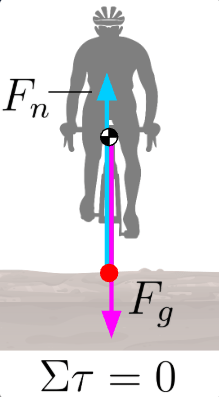

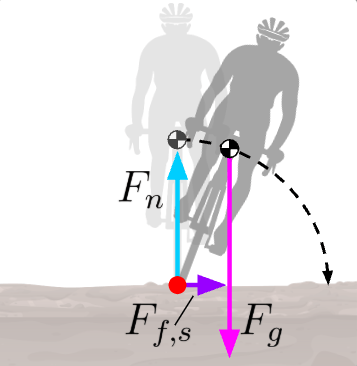

When viewed head-on, the bike and rider can be viewed as one system (the bike-rider system) that rotates about an axis located where the wheels contact the ground. Since the normal force and static friction act at the axis, they cannot produce torque.

However, the force of gravity can produce torque, as it acts at the system’s center of mass, not at the axis of rotation. Notice my deliberate choice of “can.” I use this word because, along with every force, it will only produce torque when it has a component that is perpendicular to its position vector. In the diagram below, the force of gravity is directly above the axis of rotation. Therefore, there is no component perpendicular to the position vector.

With the center of mass directly above the axis of rotation, the net torque is zero, and the bike-rider system remains comfortably in rotational equilibrium.

If the rider leans right (according to our perspective), however, the system’s center of mass becomes unaligned with the axis. This causes a component of F_g perpendicular to the position vector to arise, thereby initiating a torque (and, if you don’t control it, a painful fall!).

We’ve all been there.

You can imagine this happening also without the rider (e.g., if you just tip over a bike). The center of mass no longer rests directly above the axis of rotation, leading to a perpendicular component of the force of gravity which then causes a torque. Kickstands are used so that the normal force exerted by the ground on them can cause a torque that opposes gravity’s, bringing the system to rotational equilibrium.

As an interesting side note, when the rider leaned, their center of mass accelerated rightward. The center of mass only accelerates from a net external force. Here, the net external force was static friction! The wheels have a tendency to slip outward; thus, static friction pushes in the opposite way, causing the center of mass to accelerate, as shown above. (Recall that static friction opposes the tendency of motion.) Without the presence of static friction (e.g., the system is on ice), the wheels would slide out of the way as the center of mass accelerates down but not laterally.

Tires on inclines

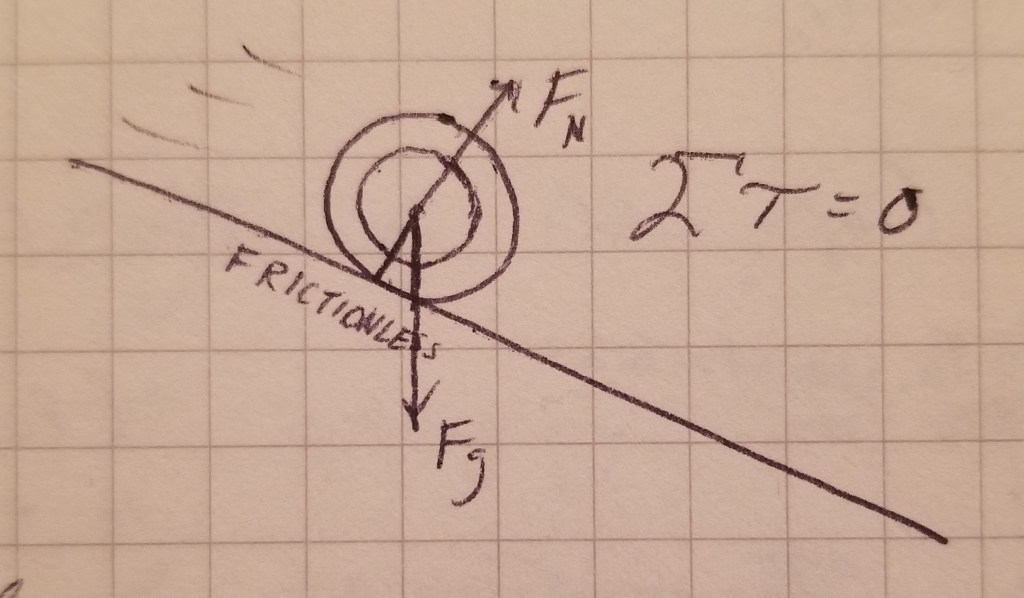

Suppose a tire is on a frictionless hill. Only the force of gravity and the normal force act on it, but since the force of gravity acts at the axis of rotation (the geometric center) and the normal force goes through it, the net torque is zero and the system is in rotational equilibrium. However, the component of gravity parallel to the surface causes the tire to accelerate downhill.

The tire therefore slides down the hill without rotating.

If static friction is present on the incline, it would be pointed up the hill in order to oppose the wheel’s tendency to slip down the hill. Since such friction is perpendicular to the position vector, it causes torque and thus rotation. The parallel component of gravity still accelerates the tire down the hill, of course.

The tire therefore rotates and accelerates down the hill. It is neither in rotational equilibrium nor in translational equilibrium.

Because static friction opposes the linear motion, the wheel on a friction incline accelerates slower than the wheel on the frictionless incline.

It’s hard not to wonder why the universe is comprehensible at all. Even something as seemingly complex as bike riding can be, with careful study, reduced to fundamental laws and have its complexities be seen as a misunderstanding on our part. God must have taken pity on us simple-minded creatures.

This article has had the desired effect of satiating my appetite for bike riding. However, it turned out to not have been necessary, as this weekend will be in the upper fifties. Time to overcome that activation energy!